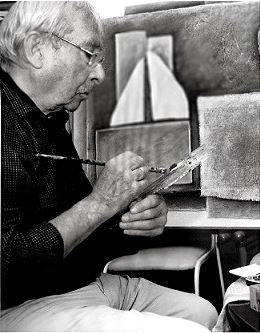

Vicente Castellano

A painter of integrity, in the words of Juan Manuel Bonet, Vicente Castellano (Valencia, 1927-2014) travelled to Paris in the mid-1950s, where he remained for two decades. He lived for a couple of years in his Colegio de España, which would prove so fruitful for our creators. That city, as for so many artists of those years – Chillida, Palazuelo, Sempere and Lucio Muñoz – was, in his words, “an extraordinary discovery”. Sempere would then be his great companion, an extraordinary tutelary shadow – in his words – who would initiate him into the artist of mystery, Paul Klee. A participant in one of the first attempts at artistic renewal in Valencia, the group called “Los Siete” (1950-1954), and a member from the beginning of the “Parpalló” collective (1956-1961), Léon-Louis Sosset would refer at that time to the “strange refinement of the materials (…) and the lively balance of colours and forms”, comparing his work to Schwitters. He studied at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris with the painter Edouard Goerg.

A student of space, textures and forms that had already impressed some cubist painters, his “recovery” as an artist, so closely linked to international currents, but far removed from the noise of informal art, had to do in our time with his Valencian galleries, first Muro and then Rosalía Sender, and with the defence of his work by Bonet’s IVAM.

A recent retrospective of his work, held in 2010, finally allowed many to become acquainted with his work, in which, together with this spatial reflection, there was a highly objectual sculptural world, variegated “reliquaries” in his own words, seeming to be a cross between Nevelson and Rueda.

A highly refined artist, a painter fascinated by the elusive miracle of simplicity, in the words of his artistic companion Vicente Aguilera Cerni, his creative career has been extremely singular and heir to that statement by Herbert Read: the artist is always an outsider.

Like his admired Parisian Juan Gris, Castellano became a painter of a different time, seeming to have given priority to his inner voice. Some have interpreted his painting as being permeated by an indefinable melancholy accompanying the slow rhythm of his forms and structures, the delicate superimposition of planes of colour, the sobriety of his monochromatic reliefs, the disciplined tempest that bathes his collages of materials. Castellano is an artist to whom one could apply that maxim recalled by Jean Cassou: he was a being endowed with a rare character of perfection and purity.

Castellano was an advocate from his beginnings, also in writing, of the transcendence of art, of the understanding of art as a factor of emotional enrichment, art as a prosecutor of plenitude. Thus, it is not surprising that Castellano declared that “the artist makes a subjective interpretation of his reality, and in my case it has been spiritual and profound, inviting the spectator to participate in it”. For forms and lines, materials and planes, colours and non-colours, were posed by Castellano in the difficult and elusive sphere of space in search, it seems, of an elusive higher life. The eagerness to proclaim the search for an intelligent beauty was for this artist a courageous decision because it was also a sign of evidence, exposure to risk, art made completely in the open, daring to show what was, in short, the supreme exercise of faith in the craft of creation.

“He was fascinated by the elusive miracle of simplicity”, Aguilera Cerni wrote in the fifties when he discovered his work. A delicate and integral artist, I think that Castellano subscribed throughout his work, like few privileged people of our time, to the maxim of the protagonist of Balzac’s “The Unknown Masterpiece”: “You have to have faith, faith in art (…) to create something like this”.